Books read in 2010Vonnegut, Kurt. Look at the Birdie. Delacorte Press: New York, 2009.

Eugenides,

Jeffery. The Virgin Suicides. Picador: New York, 1993.

Beattie, Ann.

Where You'll Find Me. Collier: New York, 1987.

McEwan, Ian.

Atonement. Anchor Books: New York, 2001.

Brin, David. The

Postman. Bantam Spectra: New York, 1985.

Grahame,

Kenneth. The Wind in the Willows. Magnum: New York, 1967.

Remarque, Erich

Maria. All Quiet on the Western Front. Trans. A.W. Wheen.

Ballatine Books: New York, 1982.

Trumbo, Dalton.

Johnny Got His Gun.

Leigh,

Julia. Disquiet.

Brunel,

Luis. My Last Breath.

Ishiguro,

Kazuo. Never Let Me Go.

Kotzwinkle,

William. The Midnight Examiner.

1989.

Lee,

Harper. To Kill a Mockingbird.

Murakami,

Haruki. After Dark.

Vintage: New York, 2007.

Saterstrom,

Selah. The Pink Institution.

Coffeehouse Press. Minneapolis, 2004.

Kafka,

Franz. Collection.

Schochen: New York, 1995.

Baldick,

Chris: editor. The Oxford Collection of Gothic Stories.

Oxford: New York, 2009.

Gogal,

Nikolay. Dead Souls.

Robert A Maguire, trans. Penguin Classics: London, 2004.

McManus,

John. Bittermilk.

Picador: New York, 2005.

2007-2008

Books read in 2009Krusoe, Jim. Girl Factory. Tin House Books: Portland, Oregon, 2008.

50 Great Short Stories.

Milton Crane, editor. Bantam: New York, 1971.

Keret,

Etgar. The Bus Driver Who Wanted to be God.

Toby Press: Milford, CT, 2004.

Bradbury,

Ray. Something Wicked This Way Comes.

Bantam Books: New York, 1983.

Dahl,

Roald. James and the Giant Peach.

Puffin Books: New York, 1995.

Carver,

Raymond. What We Talk About When We Talk About Love.

Vintage Contemporaries: New York, 1989.

Peck,

Dale. Martin and John.

HarperCollins: New York, 1994.

Kotzwinkle,

William. Christmas at Fontaines.

Abacus: London, 1982.

O'Conner,

Flannery. A Good Man Is Hard to Find.

A Harvest Book: Orlando, Fl, 1982.

Highsmith,

Patricia. Strangers on a Train.

Norton: New York, 2001.

Mishima,

Yukio. The Sound of Waves.

Vintage International: New York, 1994.

Proulx,

Annie. Brokeback Mountain.

Scribner: New York, 2005.

Melville,

Herman. Moby Dick.

Oxford World's Classics: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Book of Jonah.

The New English Bible.

Oxford University Press, 1971.

Coetzee,

J.M. Disgrace.

Penguin: New York, 1999.

Gaitskill,

Mary. Bad Behavior.

Vintage Contemporaries: New York, 1988.

Bradbury,

Ray. Somewhere a Band is Playing & Now and Forever.

HarperCollins: New York, 2007.

Benchley,

Peter. Jaws.

Fawcett: New York, 1974.

Mowat,

Farely. The Snow Walker.

Stackpole Books: Mechanicsburg, PA, 2005.

Clarke,

Brock. An Arsonists Guide to Writers' Homes in New England.

Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill: New York, 2007.

Hammett,

Dashiell. Woman in the Dark.

Knopf: New York, 1988.

Bradbury,

Ray. “All Summer in a Day” www.wssb.org

Bataille,

George. The Story of the Eye.

City Lights: San Francisco, 1987.

Cooper,

Dona. Writing Great Screenplays for Film and TV.

Arco: New York, 1997.

Levin,

Ira. Rosemary's Baby.

Signet: New York, 1967.

Bowles,

Paul. That Sheltering Sky.

Ecco: New Jersey, 1977.

McCarthy,

Cormac. The Road. Vintage: New York, 2006.

Gilmour, David.

The Film Club. 12Books: New York, 2008.

Vonnegut, Kurt.

Armageddon in Retrospect. Berkley: New York, 2008.

2007-2008

- Dickey, James. Deliverance. New York: Dell Publishing, 1970.

- Johnson, Charles. Middle Passage. New York: Plume, 1990.

- Twain, Mark. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. New York. Penguin Books, 1986.

- Huxley, Aldous. The Doors of Perception. New York: Perennial Library, 1970.

- Ecclesaistes. The New English Bible. The Delegates of the Oxford University Press, and The Syndics of the Cambridge University Press, 1970.

- Zamyatin, Yevgeny. We. New York: Penguin Books, 1993.

- Steinbeck, John. "The Chrysanthemums." 50 Great Short Stories. Ed. Milton Crane. New York: Bantam Books, 1952. 282-291.

- Faulkner, William. "That Evening Sun." 50 Great Short Stories. Ed. Milton Crane. New York: Bantam Books, 1952. 352-367.

- Carver, Raymond. What We Talk About When We Talk About Love Stories. New York: Vintage Books, 1982.

- Johnson, Denis. Jesus' Son. New York: HarperCollins, 1993.

- Kotzwinkle, William. Elephant Bangs Train. Clinton, Massachusetts: The Colonial Press, 1971.

- Miller, Henry. Quiet Days in Clichy. New York: Grove Press, INC, 1965.

- Cain, James M. The Postman Always Rings Twice. New York: Vintage Crime/Black Lizard, 1992.

- Quiroga, Horacio. "The Dead Man." Trans. Margaret Sayers Pede. A Hammock beneath the mangoes: Stories from Latin America. Ed. Thomas Colchie. New York: Plume, 1992. 4-9.

- Conroy, Frank. Stop-Time. New York: Penguin Books, 1977.

- Ruth. The New English Bible. The Delegates of the Oxford University Press, and The Syndics of the Cambridge University Press, 1970.

- Kosinski, Jerzy. The Painted Bird. New York: Grove Press, 1995.

- Highsmith, Patricia. The Talented Mr. Ripley. New York: Vintage Crime/Black Lizard, 1992.

- Kotzwinkle, William. The Exile. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1987.

- Colette. "The Other Wife." Trans. Matthew Ward. Sudden Fiction International. Ed. Robert Shapard and James Thomas. New York: WW Norton, 1989. 67-70.

- Bowles, Paul. The Stories of Paul Bowles. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, INC, 2001.

- Gardner, John. The Art of Fiction. New York: Vintage Books, 1991.

- Mrożek, Slawomir. "The Elephant." Trans. Konrad Syrop. Sudden Fiction International. Ed. Robert Shapard and James Thomas. New York: WW Norton, 1989. 98-101.

- Mamet, David. American Buffalo. New York: Grove Press, 1976.

- Corriveau, Art. Housewrights. London: Penguin Group, 2002.

- Bellow, Saul. Seize the Day. Middlesex, England: Penguin Books, 1966.

- Miller, Henry. Tropic of Cancer. New York: Grove Press, 1961.

- Welty, Eudora. The Optimist's Daughter. New York: Vintage International, 1990.

- Maugham, W Somerset. The Razor's Edge. New York: Vintage International, 2003.

- Cortazar, Julio. Cronopios and Famas. Trans. Paul Blackburn. New York: New Direction Classics, 1999.

- Kafka, Franz. The Metamorphosis, In the Penal Colony, and Other Stories. New York: Schocken Books, 1995.

- Alameddine, Rabih. I, the Divine. New York: WW Norton, 2001.

- Gardner, John. Grendel. New York: Vintage Books, 1989.

- O'Connor, Flannery. A Good Man is Hard to Find and Other Stories. New York: Harvest Books, 1981.

- McCullers, Carson. The Ballard of a Sad Café. New York: Bantam Books, 1958.

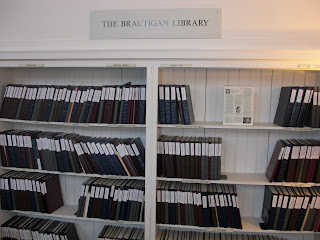

- Brautigan, Richard. The Abortion: An Historical Romance 1966. New York: Touchstone Books, 1970.

- Vonnegut, Kurt. "Welcome to the Monkey House." The Treasury of American Short Stories. Ed. Nancy Sullivan. New York: Doubleday, 1981.

- Shtyengart, Gary. Absurdistan. New York: Random House, 2006.

- Gass, William. "In the Heart of the Heart of the Country." The Granta Book of the American Short Story. Richard Ford, ed. London: Penguin, 1992.

- Keret, Etgar. “Kneller's Happy Campers.” Trans. Miriam Shlesinger. The Bus Driver who Wanted to Be God. London: The Toby Press, 2004.

- Schulz, Bruno. The Street of Crocodiles. New York: Viking Penguin, 1977.

- Frankl, Viktor. Man's Search for Meaning. Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press, 2006.

- Babel, Isaac. “Crossing into Poland.” Trans. D. McDuff. Collected Stories. London: Peguin, 1994. 199-206

- Basho, Matsuo. “The Mountain Temple,” “Narrow Road to the Interior.” Trans. Sam Hamill. Narrow Road to the Interior. Boston, Massachusetts: Shambhala Classics, 1998. 1-4, 38-41

- Forche, Carolyn. “The Colonel.” The Country Between Us. New York: HarperRow, 1981. 16

- Kerouac, John. “Desolation in Solitude.” Desolation Angels. New York: Penguin Putnam, 1995. 4-6

- Rosetti, Christina. “The Goblin Market.” Goblin Market and Other Poems, 1862. New York: Dover Thrift Editions, 1994. 1-16

- Ferlinghetti, Lawrence. “In Golden Gate Park that Day.” San Fransisco Poems. San Fransisco: City Lights Books, 1998.

- Knowles, John. A Separate Peace. New York: Bantam,1974.

- Pynchon, Thomas. The Crying of Lot 49. New York: Bantam, 1972.

- Steinbeck, John. Cannery Row. Viking: New York, 1945.

- Brown, H. Douglas. Principles of Language Learning and Teaching. New York: Pearson Education, 2000.

- Nunan, David. Ed. Practical English Language Teaching. New York: McGraw Hill, 2003.

- Louis, T.A. Things that Hang from Trees. New York: Alto, 2002.

- Haddon, Mark. The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time. New York: Vintage, 2003.

- McCullers, Carson. The Member of the Wedding. New York: Bantam, 1973.

- Faulkner, William. The Bear. New York: Vintage, 1966.

- Lawrence, D.H. The Fox. New York: Bantam, 1968.

- Yates, Richard. The Easter Parade. New York: Picador, 1976.

- Ondaatje, Michael. Coming Through Slaughter. Middlesex, England: Penguin, 1976.

- Connell, Evan S. Mrs. Bridge. Washington, D.C.: Shoemaker & Hoard, 2005.

- O'Conner, Patricia. Woe Is I. New York: Riverhead Books, 2003.